Leading in the Public Interest

Public interest is defined as “the benefit or advantage of the community as a whole; the public good”

The overall outcome of new public leadership is the creation and demonstration of public value (see Mark Moore (1995)).

Social value acts as a foundation for the consideration of leading in the public interest and in understanding this as an objective rather than subjective measure. Although social value is taken to be more relevant to the leadership of public services, it is argued that it is of equal relevance to the private sector in what is becoming popularly referred to as ‘shared value’.

‘Social value’ suggests that it is society — and not the individual — which sets a value on things although we must of course acknowledge that society comprises individuals and, as we know, individual values are more subjective. The key test – particularly within the context of mass media in contemporary society – is how to capture the collective spirit of social value as, in general terms, society does not meet to find out the wants of the community. A more recent means of both identifying and responding to social needs is through the concept of social entrepreneurialism that spans both the private and public sectors and, with the exponential increase in social media, and the growing interest in crowdsourcing. Porter and Kramer tell us that a focus on shared value is the only way in which business can rebuild its legitimacy which they describe as having “fallen to levels not seen in recent history”(Porter and Kramer, 2011: 4).

Although there has been a push by many companies to demonstrate social responsibility, the authors argue that this is at the periphery rather than the core of business and that the concept of shared values “recognises that societal needs, not just conventional economic needs, define markets” (ibid: 5).

This represents a significantly new challenge for private sector companies and an opportunity for leading in the public interest.

Public Value

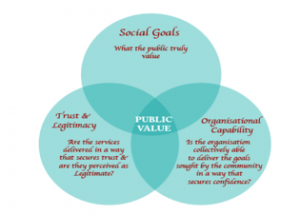

Public value appears to be a wider framework for considering the outcomes of leading in the public interest and it is argued that social value is one of three values that underpin the overarching public value framework, in addition to economic value and political value. Each of these terms will be discussed shortly but before doing so, let us consider the three key elements to the concept of public value (Moore, 1995). The first is what is Moore describes as social goals, the second relates to the way in which those goals are secured through organisational capability and the third relies upon this delivery building both trust and legitimacy.

We can now explore the three forms of public value:

Social Value

Social value, as described above, is created when resources, inputs, processes or policies are combined to generate improvements in the lives of individuals or society as a whole. It is in this arena that most non-profit organisations justify their existence, and unfortunately it is at this level that one has the most difficulty measuring the true value created. Examples of social value creation may include such “products” as cultural arts performances, the pleasure of enjoying a hike in the woods or the benefit of living in a more just society.

Economic Value

Economic value is created by taking a resource or set of inputs, providing additional inputs or processes that increase the value of those inputs, and thereby generate a product or service that has greater market value at the next level of the value chain. Examples of economic value creation may be seen in the activities of most for-profit corporations, whether small business, regional or global. These principles also apply in public leadership contexts.

Political Value

This is the least understood of the three public values. Politicians fulfil a different role to those of organizational or institutional actors. Within a democracy, political value also has importance. Moore argues strongly for political management in mitigating the various wants and needs within the resources available and in securing delivery that is perceived as legitimate and trusted by the public.

The Role of Values in Shaping Behaviours

Values and behaviours can have a significant impact on leading in the public interest. We can ask:

“why are leaders motivated to lead (whether for selfish or selfless reasons)” and “why do others either co-produce that leadership or simply follow?”

It is about context and realism in its many forms and selfless leadership holds some promise in being able to unpack the black box of leadership within this complex social world of interacting contexts.

It is a fact of life that selfish behaviour will often predominate over selfless behaviour. Working to a sense of shared values and shared purpose can be very difficult.

Selfless leadership is about putting the wider public interests over and above a leaders own personal interests. The same applies at an organisational level. Individuals have ego’s and so do organisations, and it is often ego’s that act against selfless and public interests. To lead in the public interest, means leaving ‘Ego’s at the door!

The All-Important “How” Question

One of the key skills of a leader is in balancing the head and the heart in encouraging the hand.

One of the key omissions in contemporary leadership is the inclusion of the heart in asking the question;

“Are we doing the right things for the right reasons?”

It may thus be evident that another key skill of a leader is to ask the intelligent questions. We can indeed look back in history in understanding the ethical and moral grounding for leadership in setting the right context for the right questions.

Practical wisdom (phronesis) is the intellectual virtue concerned with doing

Aristotle, arguably one of the most eminent of Greek philosophers, distinguished the word phronesis from other forms of wisdom (such as episteme and techne) relating it more to practical wisdom rather than simply intellectual wisdom but within the context of ethics. This aligns well to the notion of the practice of leadership and, in particular, the requirement to lead in the public interest. Theories can only be useful if they improve the practice of leadership.

| Has there been too much management and not enough leadership? |  |

Leadership theories began their journey focused on the innate qualities of an individual. This then evolved to a study of the behaviours adopted, the situations in which leader- ship takes place and leadership that is specific to particular functions. These theories have their place but arguably they tend to ignore leaderships’ increasingly important dynamics within a changing context of uncertainty.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]